As testers, we often hear about the Software Testing Pyramid. I myself have talked about it many times on my blog and on my podcast.

What is the Testing Pyramid?

For those of you that aren’t familiar with the testing pyramid, it’s basically a way to break down the type of test case distribution you should have for testing your development efforts. This breakdown resembles a pyramid and is one of the more popular concepts QA teams use when planning their testing efforts.

Unit Tests makes up the largest section of the pyramid, forming a solid base. Unit tests are the easiest to create and yield the biggest “bang for the buck.” Since unit tests are usually written in the same language an application is written in, developers should have an easy time adding them to their development process.

The middle of the pyramid consists of Integration Tests. They’re a little more expensive, but they test a different part of your system.

GUI testing is at the top of the pyramid and represents a small piece of the total number of automation test types that should be created.

The Testing Pyramid is Flawed

Sounds reasonable, but I think a concept can sometimes be misused and misunderstood. And honestly, sometimes the testing pyramid itself is misleading. I spoke with Todd Gardner of TrackJs recently, and he believes that the testing pyramid concept is flawed for two main reasons.

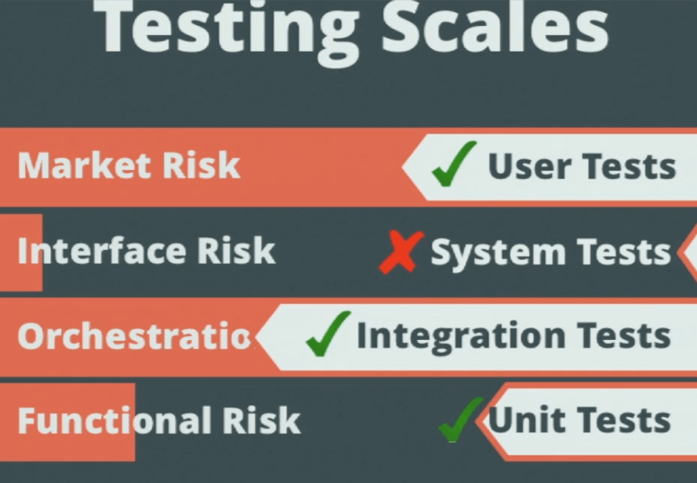

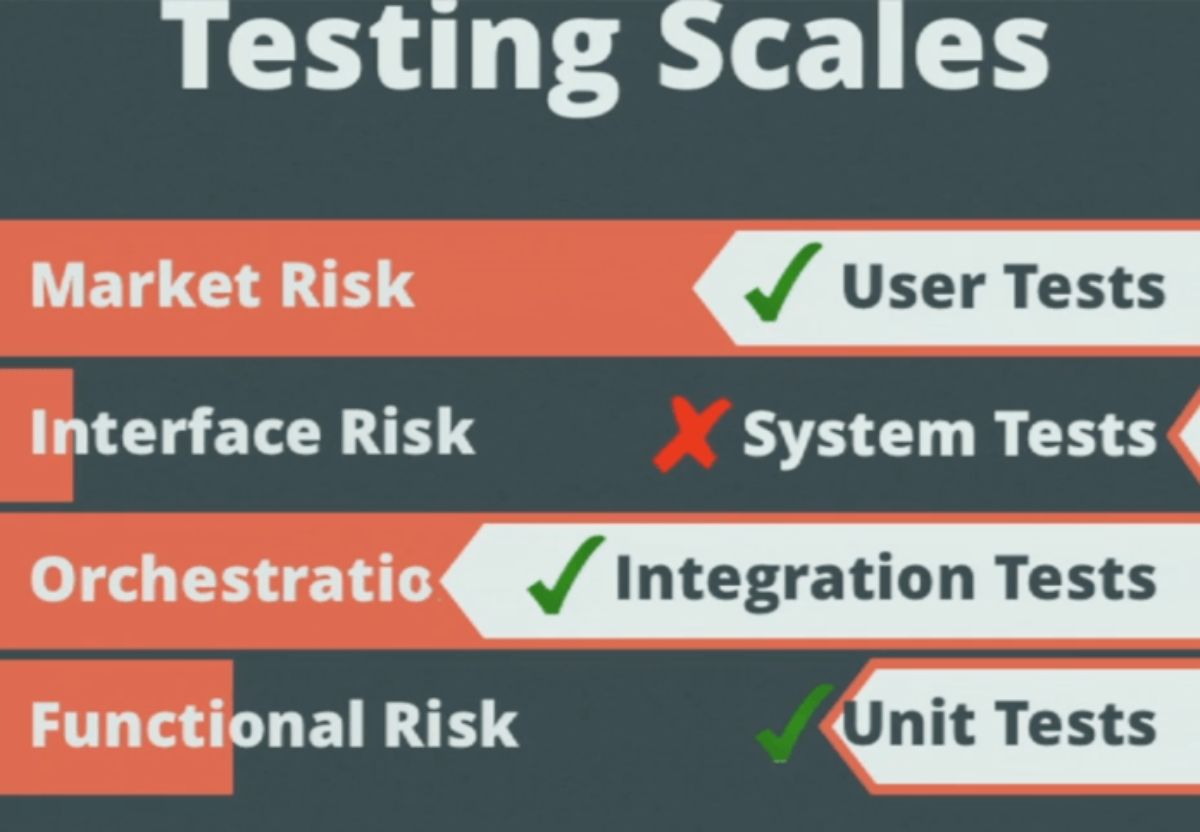

The first reason is that it misses market risk. Determining whether or not the project itself is a good idea, and how do you test that? In other words, operating at a level above system tests.

Todd’s second problem with the model is that it implies volume. It’s basically saying you should have more unit tests than integration tests because unit tests are cheap to write — and he believes that’s missing the point. It shouldn’t be about how what it costs to write and maintain, but rather what kind of risks are being addressed by these sorts of tests.

[tweet_box design=”box_3″]The question of “Are you testing the right thing?” I don’t think is asked often enough, because it’s really hard~@toddhgardner [/tweet_box]

Does it always make sense to adhere to the Testing Pyramid?

Todd goes on to say that a lot of web applications he tends to write today are really trivial. He’s simply trying to demonstrate a concept, or attempting to build a CRUD App for some purpose, and he’s basically converting SQL into HTML and back. In those sort of apps, there’s very little functional complexity happening. Normally, you have a framework that you’ve shoved in place that’s handling and abstracting all that stuff away.

He doesn’t really see much risk in the functional logic at that level, so he tends not to write many unit tests in that situation. If it works, it works, and if it doesn’t work, it’s not going to work. There’s not a whole lot complexity at that level.

There is complexity, however at an integration level: “Can my app talk to my database?” and, “Am I writing queries correctly?” Todd will write some integration tests around that. “Am I presenting a user interface that makes sense?” He’ll write some system tests around that.

Depending on the app, he might have completely inverted the Pyramid. He may have ten system tests, five integration tests, and one unit test for the one actual, interesting piece of logic he had in an app, which totally messes with that metaphor of a “pyramid.”

Scales, not Pyramids

Todd firmly believes we should think scales instead of pyramids when it comes to software development testing. Rather than prescribing how many of one kind of test you should have over another, you should look at, say, “What kind of risks exist in my system? How can my system break?” and build up the testing coverage that you need in each of those areas to address the risks of the system. Software development and testing are really all about risk.

What is Software Risk?

As Matt Heusser from Test Talks Episode 61 explains it,

“We can look at the risk of building the wrong thing that is not going to be fit for use. That’s product risk.

We can look at the risks that are injected from theory that we learned from a book, and then try to implement that process on our teams only to find that it doesn’t really work for us, and that’s process risk. Of course, there’s a software buggy risk.”

[tweet_box design=”box_3″]The Heuristic Test Strategy Model has a half-dozen different ways to look at all the risks on a project~@mheusser [/tweet_box]

It all about Risk

So how does risk fit into our testing efforts? Matt recommends using the Heuristic Test Strategy Model, which has a half-dozen different ways to look at all the risks in a project.

If you go through all the risks on the project in a systematic way, you identify which risks you want to do something about. You figure out the kinds of different ways you can address those risks, and you stand that up against the consequences. If those things break, you sort that, and you go through it until you run through the amount of time you’re willing to invest.

That’s a whole lot more responsible. It’s better testing than the kind of requirement-based testing that many testers end up following.

Learn More

- How to Reduce the Cost of Software Testing – Matt Heusser

- Case Studies in Terrible Testing Todd Garder 2015 OreDev video presentation

Joe,

Interesting POV on this one. One of the things I’ve seen misunderstood regarding the Test/Automation Pyramid is the intent/purpose of those tests at the different levels. The reason, I believe, that Mike Cohn stated that you will/should have more Code/Unit level tests is because of the level of granularity (or atomicity as some people call it) at which these occur. The Unit Tests are supposed to exercise code (statement and logic) to make sure it is processing correctly or not (Assertion). Thus because of this fine granularity you would naturally produce more of those tests/assertions. By doing so you make sure the rudimentary logic and functionality of the code is sound before moving down the line. These are typically the types of simple mistakes (basic logic & functionality) made by developers that later on cause a build to rejected, thus causing rework churn and lost time. Supposedly the greater amount of coverage at that level helps to reduce risk to work effort later on.

And so on and so forth for the other layers of the pyramid. Thus at the upper levesl the “granularity” of the test becomes more coarse and not as many may be needed because you are doing a multi-layer approach. Which seems all good in theory, but as you point out in practice may not be the reality of the situation.

I don’t believe that Mike Cohn was trying to make this a hard/fast rule, but more of a guideline of what ‘could’ occur if a team is truely using agile practices methods to produce and test its code/software/system. Again in theory it looks good on paper, in the real world it could be an absolute mess.

Joe,

It’s easy to get caught up in the moment land forget anout the basics (e.g. why we test, where the risk is, etc.). So thanks for reminding us of this!

Joe,

It’s easy to get caught up in the moment and forget about the basics (e.g. why we test, where the risk is, etc.). So thanks for reminding us of this!

Thanks Colin! It was great meeting you in London

http://steveo1967.blogspot.dk/2015/10/mewt4-post-1-sigh-its-that-pyramid.html

John Stevenson writes a similar conclusion, yet coming from another direction.

Cool Thanks Jesper! I also noticed that John and Richard also created some videos around this: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/whiteboard-testing-new-videos-richard-bradshaw